Prediction aligns with one US analysis that existing schools sufficiently boost supply

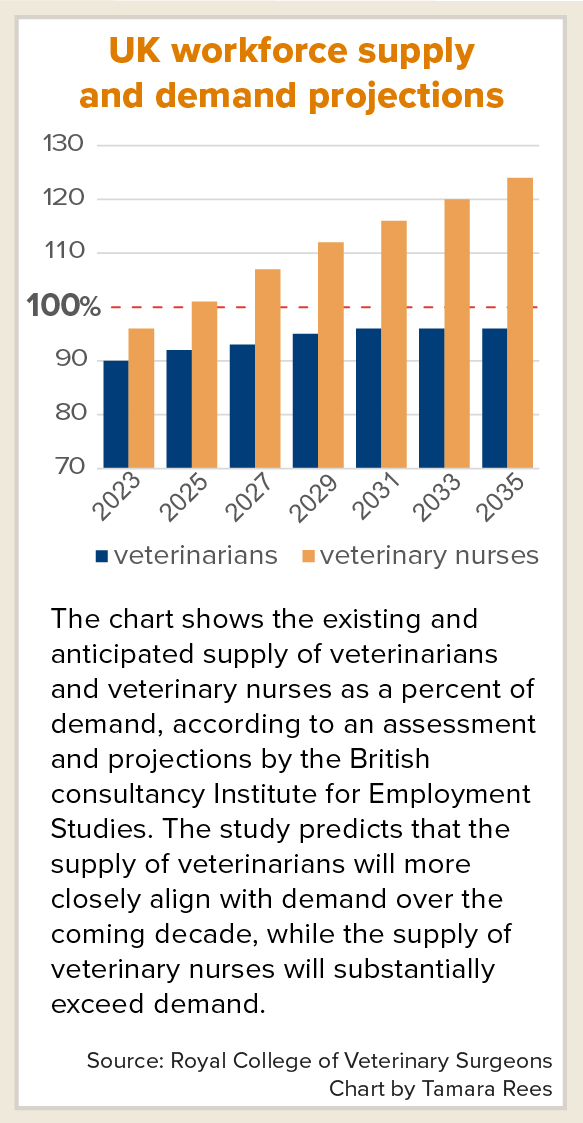

UK workforce supply and demand projections

Listen to this story.

Listen to this story.

A shortage of veterinarians in the United Kingdom will gradually ease over the next decade, bringing the supply of practitioners almost into line with demand for their services, according to an assessment commissioned by the country's official regulator for the profession.

Produced by the Institute for Employment Studies on behalf of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS), the report also predicts that the U.K. will experience a considerable oversupply of veterinary nurses, whose role is similar to that of veterinary technicians in the United States.

The report's findings provide a sign that some — but not all — forecasters believe that a tight labor market for veterinarians on both sides of the Atlantic pinned on everything from a pandemic pet boom to retiring baby boomers could be alleviated by cooling demand and existing schools, some of which have expanded their capacity and some of which are new.

Last month, a study published in the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association posited that supply and demand data "do not support an expectation of a continued shortage" of veterinarians in the United States. Its findings were contrary to two other recent U.S. studies.

For their part, the British researchers found that the supply of full-time equivalent veterinarians in the U.K. met 90% of demand in 2023 and is projected to increase to 96% in 2033, then drop off "very slightly" by 2035. The remaining shortfall largely would be among veterinarians working in government services and other nonclinical roles. Among veterinarians working in clinical practice, the report projects that supply will increase to nearly 99% of demand in 2035, compared with 91% in 2023.

Overall, the researchers expect the number of veterinarians in the U.K. to jump 52% between 2023 and 2035 to around 44,800.

"This continues the trend over recent years, and is largely due to the number of joiners and re-joiners being greater than the number of leavers each year," the report states. "Furthermore, the number of joiners in the future will be boosted by the new vet schools coming on line in the next few years (although graduate numbers are projected to be steady from 2029 onwards)."

Among new veterinary schools, the University of Central Lancashire welcomed its first student cohort in September 2023. That group will complete the five-year undergraduate program in summer 2028. (Veterinary medicine in the U.K. typically is studied at the undergraduate level). A new veterinary school at Scotland's Rural College debuted this year. Its first class of students will graduate in 2029.

The rising number of graduates doesn't necessarily mean the U.K. will be free of supply issues by 2035, according to Ben Myring, policy and public affairs manager at the RCVS. He noted, for instance, that the report projects a large shortage of veterinarians in public health roles, for which supply is expected to remain below 80% of demand by 2035.

"It's not just about the overall figures; it's about where there's going to be continued shortage and even slight fallbacks in areas that are absolutely critical," he said during a press briefing about the report. "And by relieving the shortage in clinical work, that could then mean that you could think about veterinary practices having time to have some of their vets also doing work in public health, for instance."

Myring acknowledged that predicting demand and supply is "fiendishly complicated," noting that the modelers' calculations accounted for a variety of factors, such as gender, nationality and part-time work levels.

"This is a future-gazing exercise but based on data," RCVS Research Manager Vicki Bolton said during the briefing. "So this is not guessing at big changes that may happen. It's not looking for the meteor strike. This is using past experience to project what we think will happen in the next decade."

The projected outcomes could be adjusted in the event of a large shock, she said. "So we can imagine what would happen to the supply of vets if a vet school closed, or if there suddenly was a push by Australia to employ more U.K. vets."

Is an overabundance of veterinary nurses imminent?

One striking finding of the British research is that the supply of veterinary nurses, found to meet 96% of demand in 2023, will exceed demand next year, then reach a surplus of 22% over demand by 2035.

The mismatch has less to do with new people joining the field and more to do with fewer leaving.

"The veterinary profession is extremely well-established, and there are plenty of people practicing up to and, in fact, beyond normal retirement age," Bolton said, "whereas vet nurses haven't had that opportunity yet. So the first registered vet nurses, those cohorts haven't yet reached retirement age."

The role of veterinary nurse was formally recognized in U.K. law in 1991.

Bolton cautioned that the researchers' modeling didn't take into account how employers might respond to changes in demand and supply — for example, by cutting wages — and how such responses might skew the projections.

"Again, this is based on the demographics between 2017 and 2023 projected forward," she said. "So this is if nothing changes."

US study predicts cooling demand

Opinions on supply and demand dynamics in the veterinary profession aren't uniform, not least in the U.S., where there is much contention over what the future holds.

At least two studies published in the last year or so have forecast a persistent shortage of practitioners.

In March, the American Association of Veterinary Medical Colleges, which represents veterinary schools, published research estimating that 52,986 graduates will join the U.S. workforce through 2032, providing just 76% of the 70,092 new veterinarians that the researchers projected the country will need. The report was criticized by the American Veterinary Medical Association, which opined that the researchers had overestimated demand and underestimated supply.

The AAVMC-commissioned study was soon retracted, not due to that criticism but because, the AAVMC acknowledged, some of the language in the original report didn't respectfully recognize the increasing role that women play in the profession. The report was revised and republished in June with the workforce prediction unchanged.

Separately, a study published last year commissioned by Mars Inc., which owns around 3,000 veterinary practices worldwide, predicted that a shortage of 14,000 to 24,000 companion animal veterinarians "could well exist" in the U.S. by 2030, "representing an overall shortfall of veterinarians of approximately 11% to 18%."

The latest study, published in JAVMA in November, challenges those predictions, in part by maintaining that there has been a "return to normal" demand as a pandemic pet boom fades.

The study was commissioned by the AVMA. Its three authors are with Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine, Brakke Consulting and the AVMA. They maintain that rapid increases in the cost of veterinary care have dampened demand, helping to bring demand and supply back into balance.

"Current data do not indicate a persistent labor shortage but a well-functioning market where veterinary service prices have increased more rapidly than in the rest of the U.S. economy," the report states. "Recent data indicate a slowing and slight reversal of growth in revenues and visits to veterinary clinics."

There are currently 34 accredited veterinary schools in 27 states and one territory, including four that have opened since 2019. Another nine programs have been proposed; two aim to open in 2025, six in 2026 and one in 2027.

The research published in JAVMA indicates that existing educational infrastructure in the U.S. already is sufficient to meet demand for the next 10 years, John Volk, a senior consultant at Brakke and a co-author of the study, said in an interview.

If more planned schools come on board, Volk said, "long term, it's going to take some sort of greater increase in demand to absorb all that labor without putting downward economic pressure on the profession."

The researchers acknowledge their study has limitations: "The methods we present in this paper allow for the ready adaptation to new data. However, they represent only an initial step in modernizing forecasts of veterinary labor markets."